Win at Life

The Gottman Ratio comes from decades of research at The Gottman Institute, a relationship research and training centre in Seattle, founded by psychologists Dr John and Dr Julie Gottman. They found that relationships with staying power typically have a healthy balance of positive to negative interactions.

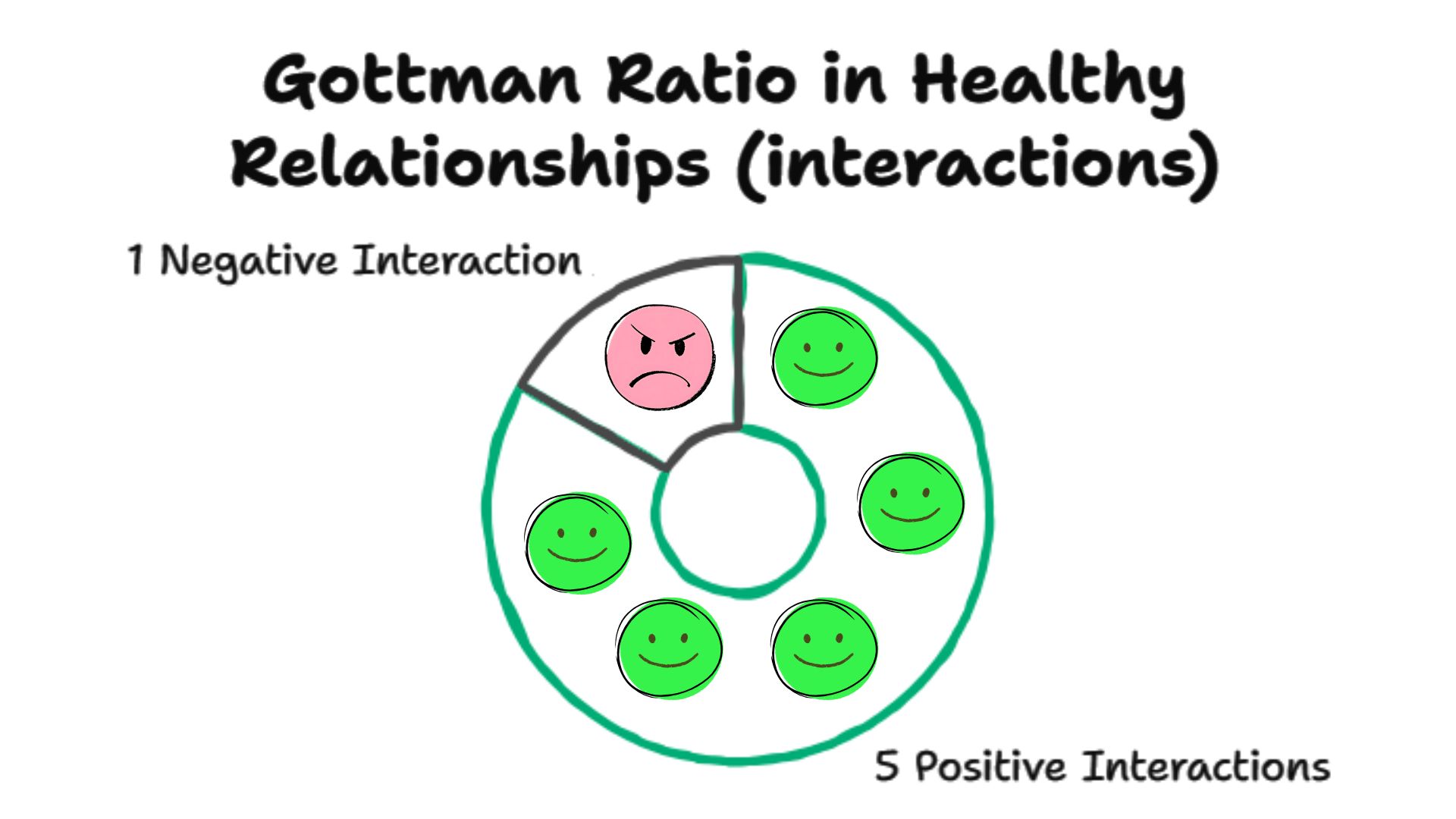

Specifically, their research found that five positives for every one negative was the sweet spot, particularly during conflict. If couples can maintain the 5:1 ratio, flooding the negatives with, for example, curiosity, humour, warmth, respect and interest, then difficult conversations don’t damage the relationship.

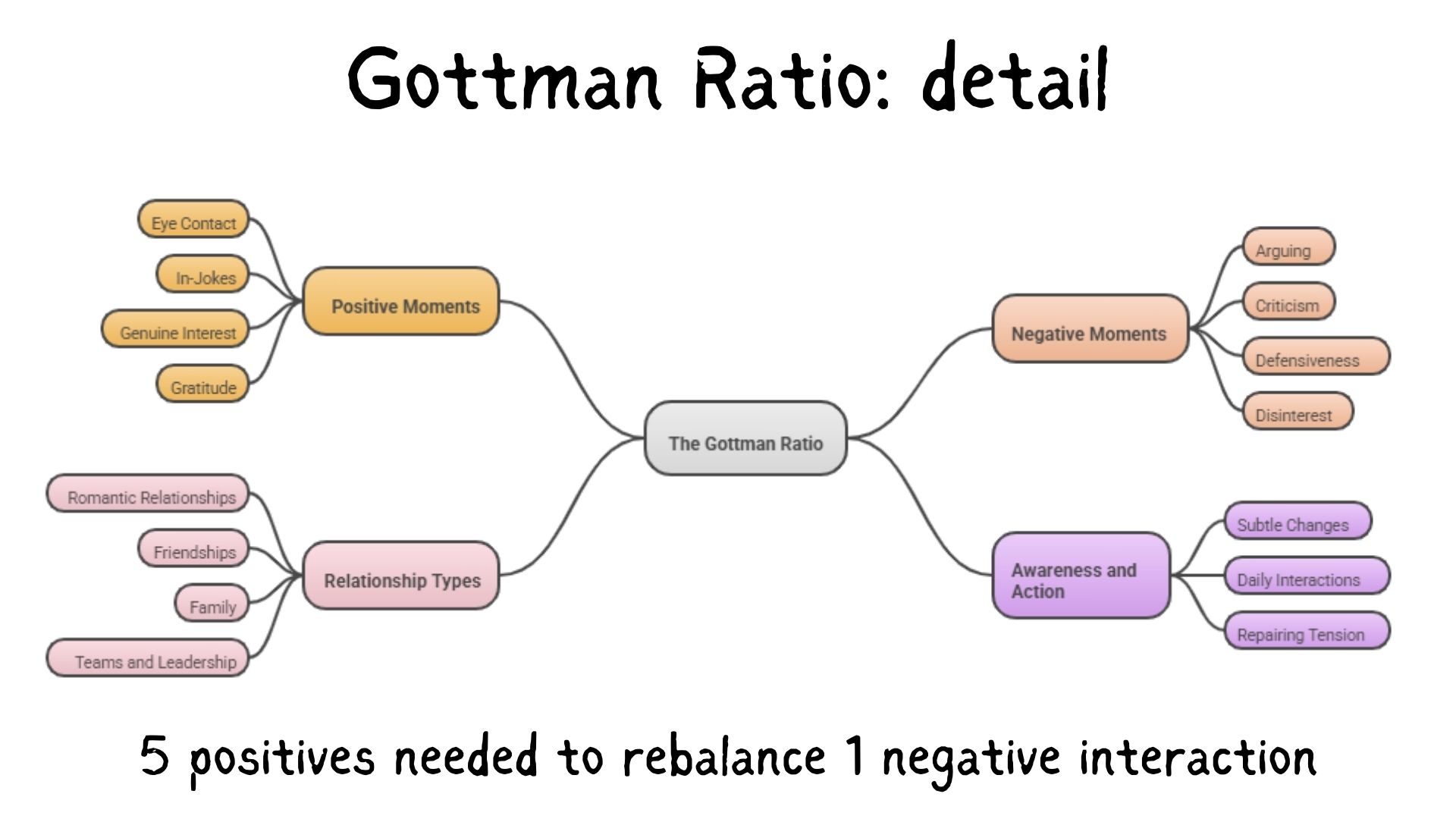

Although the original findings came from romantic partnerships, the principle applies just as much to friendships, families and professional relationships where trust and honest communication matter. (Which, let’s be honest, is most of them).

What it is and why it matters

The Gottman Ratio is a measure of the overall atmosphere of a relationship, about balance rather than ‘rom-com’ perfection.

Positive moments include even the tiny things like eye contact, in-jokes, a question asked with interest, or a thank you for something ordinary.

As well as the obvious arguing, shouting, etc, negative moments might be irritation, criticism, defensiveness, passive aggression or simply disinterest.

When your positive moments outweigh the negative ones, the relationship tends to feel closer, more connected, and nicer to be in. Arguments are over more quickly, tensions easily dissipate, and little things don’t spiral into something more dramatic.

But negativity becomes the dominant tone of the relationship, then you’ve got problems.

You start tiptoeing around the subject – walking on eggshells and not saying important things because you know it won’t be well received.

This chips away at the connection, an emotional distance starts to grow – and the sense of goodwill towards the other drains away.

‘What did I even see in them?

What was I thinking?‘

The Gottmans also found something many couples recognise.

One partner will sometimes say they had “no idea” their partner was considering ending the relationship, while the other can’t believe their partner managed to miss their clear messages of dissatisfaction for years.

The research suggests that this gap is often a sign of years of missed positive moments, unacknowledged bids for connection, and a climate that tipped towards the negative long before separation was ever mentioned.

How it plays out in different relationships

Romantic relationships

In strong couples, positive moments are sprinkled throughout the day. Humour, little kindnesses, stopping what they are doing to turn and fully listen to the other.

These, the Gottmans found, are the glue that holds partnerships together.

Long-term decline is rarely one big thing, but tends tends to come from repeated micro (or even macro)-neglect, overt/or direct ats of disrespect, rising tension and not enough positive interactions to counterbalance them.

Friendships

People stay close because they keep catching each other’s small cues, however often or rarely they see each other.

When a friendship loses its usual ease, it’s often because the positive moments have thinned out, or it’s become one-sided.

Without the positives, the dynamic becomes functional or even historical, rather than emotionally supportive.

Family

Warmth and acceptance play a huge role here.

Parents who mix guidance with connection tend to create environments where children feel secure enough to cope with stress and express themselves.

An environment that’s not quite ‘I’d bury a body for you’, but messages of ‘I have absolutely got your back, even if I don’t 100% understand your choices’ – is what makes the trickier conversations possible, later.

Teams and leadership

I couldn’t find an official workplace ratio, but psychology research shows that teams with a higher proportion of positive interactions communicate better, innovate more, and feel safer speaking honestly. Leaders who encourage curiosity, fairness and celebrate each other create a safe environment, which is the foundation of all meaningful working relationships.

How awareness helps

This isn’t about keeping score or pretending everything is lovely. It is about noticing the tone you bring into your interactions. A few subtle changes make a surprising difference.

Look up a little more often.

Answer the small bids.

Repair sooner rather than later when something feels off.

Let your warmth be visible, not implied.

These shifts turn daily interactions into connection rather than friction.

Try this today

Pick one relationship that matters to you.

Offer three small positives today.

A moment of interest.

A brief smile.

A thank you.

A question asked with genuine curiosity.

Notice how quickly the tone shifts between you.

Things to think about

Where are you generous with your positives, and when do you feel that you hold back a bit?

- Where do they taper off?

- Which relationships have become more negative than you realised?

- How quickly do you repair tension?

- How quickly do they?

- What atmosphere are you unintentionally creating?

- Which relationships already feel grounded and connected, and why?

- Which ones need some serious attention? Or distance?

Optional challenge

Over the next few days, if a difficult moment happens, offer something positive within the next interaction.

Not to balance the books (although that, too), but to bring the tone back into a place where conversation feels possible rather than fraught.

A Buddh-ish take

Buddhist teachings often remind us that the quality of our attention shapes the quality of our relationships.

Every interaction is a small vote for connection or distance. The Gottman Ratio is simply the psychological version of this idea.

As we read in the Dhammapada:

“Speak with kindness and your words will echo in the hearts of others.”

Connection grows in the small, consistent moments.

A softened tone where it might have been harsher, a small pause to listen rather than scrolling and half-listening. A gesture that says, I am here with you. These are the threads that hold relationships together over distance.

Back to Mindset Mechanics <

Back to The Vault <

References

Gottman, J. M. (1994). What Predicts Divorce? Psychology Press.

Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (1992). Marital processes predictive of later dissolution. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(2), 221–233.

Gottman, J. M., & Gottman, J. S. (2015). 10 Principles for Doing Effective Couples Therapy. W. W. Norton.

Gottman Institute. (n.d.). Research and training centre based in Seattle, specialising in relationship dynamics.